Exploring our surrounding WiFi landscape

Nick Briz

Ever wonder how your phone is able to automatically connect to your home WiFi as soon as you walk through the door? Of course you haven’t, but you should, because it turns out this auto-connection is made possible by the fact that your phone is carelessly emitting messages, known as probe requests, in an attempt to connect to your home network everywhere you go. I say carelessly because, while they are convenient, these probe requests expose personal information about your previously connected WiFi networks which can be used to track your physical movements through a given area, determine the physical locations of where you might live, work and play and even bait your phone into getting hacked by connecting to a malicious network.

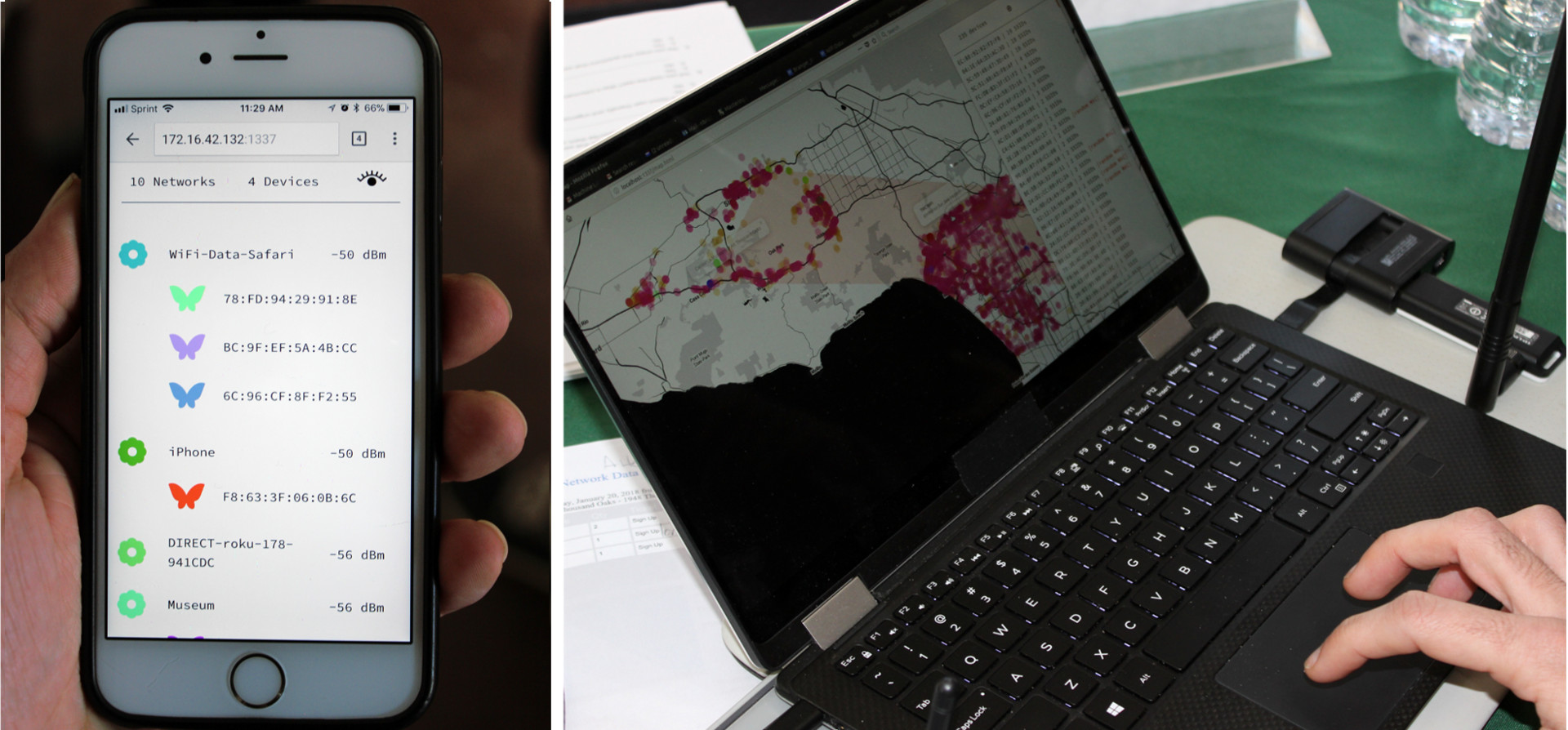

a pair of technology researchers visited Thousand Oaks to demonstrate just how inundated we are by wireless signals, and explored the potential downside to being so open.At Branger_Briz we’re driven to help people understand how technology works, so they can best decide how to use it rather than be used by it. It so happens that passively listening for and collecting these probe requests is a technique regularly deployed in different ways by hotels, government agencies, universities, shopping centers and other businesses. This is why we created Probe Kit, a generative art installation which illustrates this technique by rendering the devices of museum visitors as digital butterflies along with the personal information they’re broadcasting into the air as they walk by.

Last weekend we attended the opening of Strings: Data and the Self, a New Media Art exhibition curated by Joel Kuennen and Riccardo Zagorodnev at the California Museum of Art Thousand Oaks (CMATO) that runs until April 15 of this year. We were thrilled to be showing Probe Kit alongside some of our favorite New Media artists, Heather Dewey-Hagborg, Jennifer Chan, Shawne Michaelain Holloway and Amanda Turner Pohan.

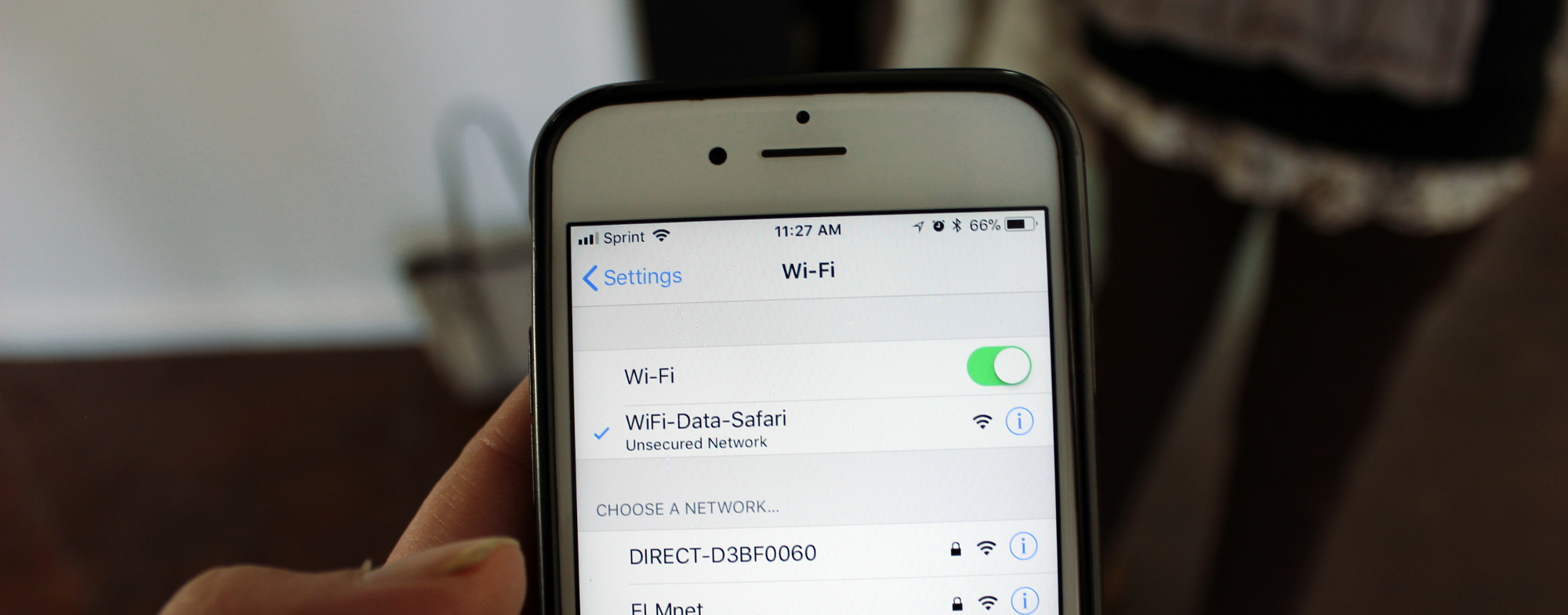

As part of the exhibition we lead a group from the Greater Los Angeles area on a "Wifi Data Safari" in Thousand Oaks. The safari was aimed at providing context for the Probe Kit installation as well as offering insight into our research based studio practice. We developed custom software that participants could access on their phones by connecting to a portable network which was constantly scanning our surroundings for WiFi activity. We discovered and discussed all manner of interesting digital activity floating around us as electromagnetic waves oscillating at frequencies lower than those of visible light.

As we walked through a park in front of City Hall we learned that the park was full of routers produced by the same manufacturer, some of which provided municipal WiFi to the park, others exclusively for city employees. There we were able to identify the devices of two residents we spotted in the park making use of the free WiFi. We explored shopping malls where we investigated the network setups of different businesses. We learned that some networks were installed only to provide customers with WiFi while others served to connect Raspberry Pi’s and tracking beacons likely set up to monitor their customers activity in the store.

At the end of the workshop we explored the data we had gathered throughout our journey and demonstrated how the probe requests we collected from pedestrians could be used to construct a map of their previously connected networks. We also showed how these probe requests could be used to hack someone’s connection to the Internet. We ended with a discussion about the different measures you can take to protect yourself from this sort of exploitation. The most important of these being the very simple act of switching WiFi off when you’re not actively trying to connect to a specific network.

Our goal with this excursion is to help people "see" the data floating all around them so that they can understand what's at stake.Our goal with this excursion is to help people "see" the data floating all around them so that they can understand what's at stake. It would be ideal if we didn’t need to worry about such exploitation, but we realize that only by bringing awareness to privacy issues like this will we ever see change. No one is going to call their congressperson asking them to pressure manufacturers to update their devices, nor will anyone demand that Android devices implement better MAC Address randomization if they don't know what a MAC Address is and why that matters.

Do you know what a MAC Address is? In a follow up blog post we’ll discuss the technical information covered during the WiFi Data Safari in-depth and share the open source software we developed for it.

Have some thoughts to share? Join the public conversation about this post on Twitter, or send us@brangerbriz.com an email, we'd love to hear what you think!