Notes From Our WiFi Data Safari

Brannon Dorsey

In our last blog post we shared some documentation from a recent workshop we gave at the California Museum of Art Thousand Oaks. The workshop was a part of a larger art show, Strings: Data and the Self, where we showed our Probe Kit installation. The installation monitors WiFi packets that are emitted from phones and wireless devices in the area illustrating the kinds of information that can be anonymously collected without their owner’s knowledge. The workshop elaborated on these ideas, educating a small group about WiFi data collection practices in the wild. For participants of the workshop, this post serves as a reference for the material that we covered during the workshop. For those of you who wandered here from the far reaches of the Internet, welcome. We hope that you will learn something while you are here, even if you couldn’t make it to the first iteration of the workshop.

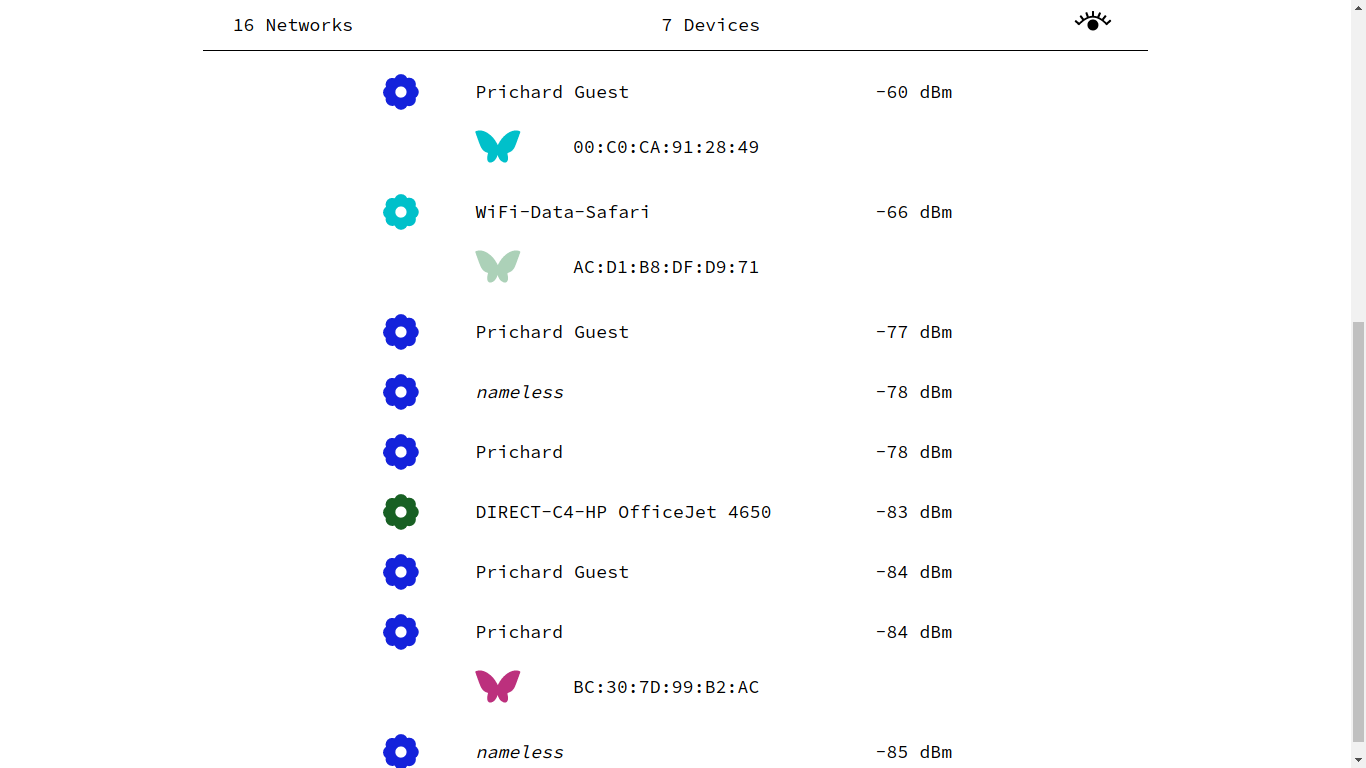

During the workshop, participants were lead through an urban environment spotting and collecting wireless signals from nearby personal devices as they traveled. Using custom software, they accessed personally identifiable data from strangers and performed targeted network attacks against volunteers, in an attempt to better understand the privacy concerns and exploitation tactics associated with WiFi. Throughout the workshop, we had conversations about information privacy and security, the shortcomings of the WiFi protocol, and the ways that companies, governments, and other malicious actors use personal wireless data.

The Internet Landscape

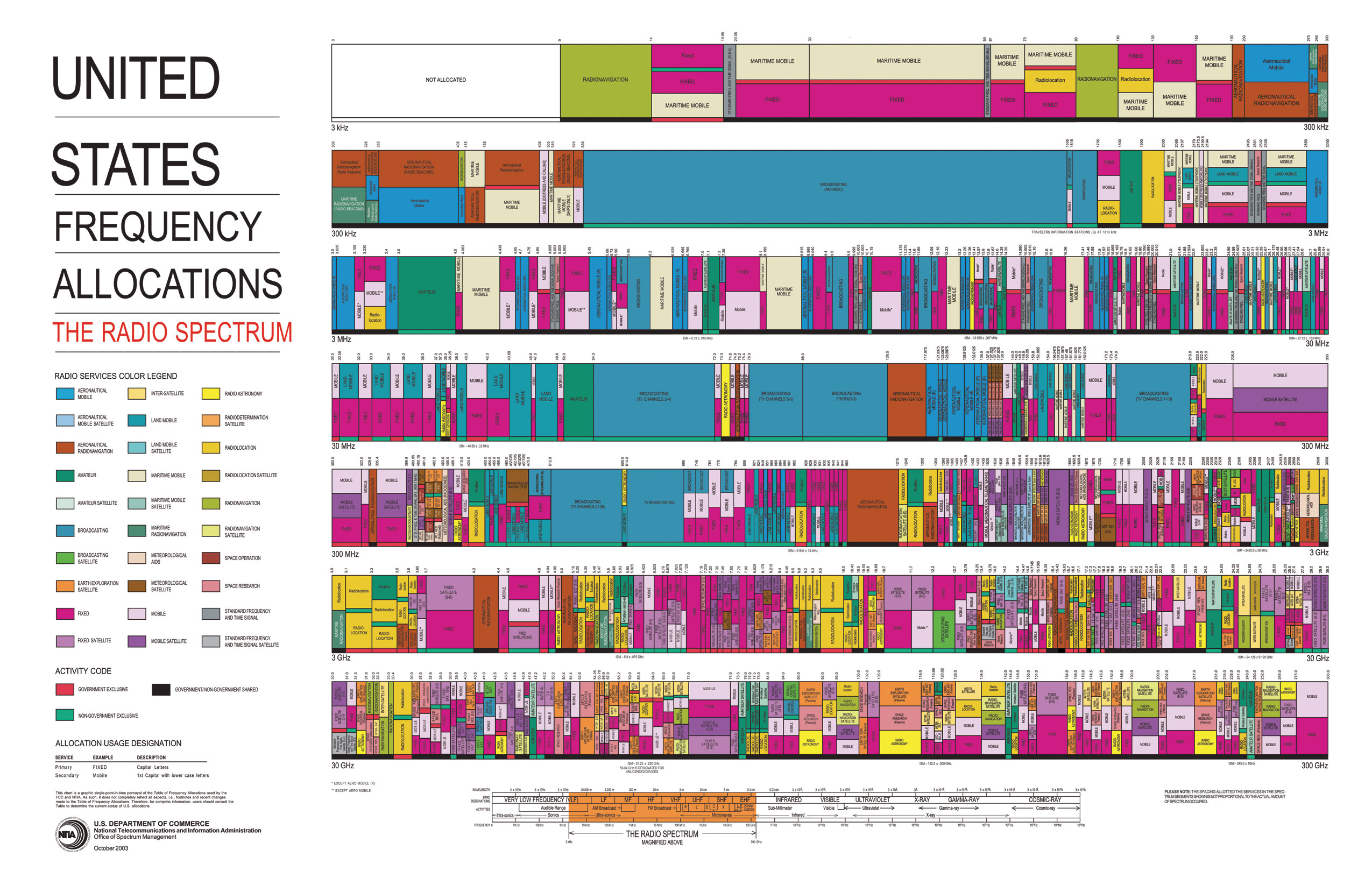

The Internet is a complex network of networks, linked together through industrial communications infrastructure. Many players are involved, from router and device manufacturers to Internet Service Provider (ISP), Tier 1 networks, Internet Exchange Points (IXP), trans-oceanic fiber optic cables, and international standards committees. Lots of machines talking to machines and people talking to people. Surprising to some, most of the Internet is connected by fiber optics and copper cable. It’s usually only the last stretch from your home router or a cell tower to your portable device that occurs over WiFi, a wireless radio frequency protocol that occupies the 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz frequency bands of electromagnetic spectrum (alongside other commercial devices like your microwave and garage door openers). It’s this protocol that we focused on particularly during the workshop.

[WiFi] was introduced without the security considerations and requirements that are necessary over twenty years later, when everyone walks around with a wireless device on their person.The 802.11 WiFi standard was introduced in 1997, before anyone had a phone that could connect to the Internet. As such, the specification was introduced without the security considerations and requirements that are necessary over twenty years later, when everyone walks around with a wireless device on their person.

Probe Requests and Beacon Frames

Ever wonder how it is that your phone auto-connects to your home WiFi network automatically without you having to explicitly authenticate your device each time? This occurs through a series of network packet exchanges between your wireless device and your home router, or access point (AP). Specifically, it leverages the use of two related 802.11 packet types, probe requests sent from your device and beacon frames sent from your access point. Probe requests are small packets of information that are emitted from a wireless device when it isn’t connected to an access point. They include two useful pieces of information, 1) the SSID, or network name, of the access point it has previously connected to and 2) the MAC address of the probing device, a unique identifier that can be used as a device fingerprint. Many devices that have WiFi enabled, but aren’t connected to a network, are constantly emitting probe requests hoping that their router will hear them and initialize an auto-connection. That’s useful if you happen to have just entered your home from work, but as we will see, it’s also identifiable information that’s openly projected from your device when you are out and about, nowhere near the router your device is attempting to connect to. In this way, WiFi devices are often constantly advertising your personal network history wherever you go, leaving a fingerprint in the WiFi radio ether for others to pick up and use.

Beacon frames serve a similar purpose to probe requests in that they exist to facilitate the authentication of devices to access points. Beacon frames contain the same useful bits of information as probes, only they are sent from access points that are advertising their existence to nearby devices. As soon as your phone sees a beacon frame emitted from the “My Home WiFi” access point, it will initialize a connection to the router. While this is helpful in the genuine case where your device auto connects to a known network, it also makes it trivial for an attacker to force a connection from your device to a malicious network by simply naming their network the same as your home network. This makes probe requests and beacon frames a lethal combination. One advertises the name of previously connected networks at all times, while the other can be used to auto-connect devices knowing only the names of previously connected networks.

Accessing Network Data

Now that you’ve learned that the network devices around you regularly broadcast probe requests, you might be wondering how you would go about accessing that data. You’re privy to seeing a list of network names on your phone or laptop (populated by the beacon frames) when you are looking to connect to a new network, but you likely haven’t ever been able to access the other packets of data hidden from normal view. You can’t see activity from other people’s devices using that familiar network drop down and you certainly can’t get list of other people’s connection histories. Instead, your operating system filters out this data, exposing only the information necessary for you to connect to a WiFi network.

Well, it turns out that many consumer WiFi cards support a special behavior called monitor mode that effectively removes this filter. Monitor mode allows your computer to passively eavesdrop on the unencrypted radio packets broadcasted nearby independent of the intended sender and receiver. Unlike a wired connection, wireless broadcast can’t be easily directed to a single device. It’s exactly what it sounds like, messages are broadly cast to all devices.

Aircrack-ng is a standard suite of networking tools that allow you to inspect and interface with WiFi data in this unfiltered manner. We’ve built custom software that sits on top of these tools and exposes the activity of probing devices and beaconing access points. During the workshop, we use this software to visualize wireless activity that is normally hidden from view.

What’s to See?

All WiFi network transmissions include a media access control number, or MAC address, that identifies which device sent the radio packet. MAC addresses are unique numbers assigned to a network interface by the manufacturer. They act as a sort of device fingerprint which can be used to identify the device, and in the case when you can tie a MAC address to the device owner, the presence of nearby human. Information about the manufacturer of the device is also embedded in a portion of the MAC address, making it trivial to identify if it belongs to an Apple iPhone or a Samsung Android phone. Other indicators can also be derived from intercepted packets, like signal strength and timestamps. When monitoring WiFi traffic, it’s not unlikely that packets with a strong signal strength are close by. Those loudly broadcast packets you keep receiving from an Apple device might just be coming from that fellow sitting next to you who is robotically thumbing through his iPhone.

Once you’ve identified which devices belong to which humans you can start to gather more information about their owners. By collecting and grouping probe requests and cross referencing their network names with other datasets, some of which are publicly available, you can begin to draw conclusions about where the device owner may live, work, and play.

War Driving and Geographic Network Datasets

War driving is the process of geo-tagging beacon frames from wireless access points in an attempt to understand where in the world they are physically located. By collecting data in this fashion, large datasets can be amassed and used to identify where the networks a device is probing for exist in the real world. In fact, Google street view cars have been reported to be constantly war driving, creating collection of geo-tagged networks to use in their location services. By using cars, and even their user’s android devices as they go about their daily life, Google can create complex maps of beaconing networks that can be used later to improve on GPS estimates, or identify where you are located even when you have GPS location turned off.

The practice of war driving is often associated with amateur network collection. The WiGLE website is a crowdsourced war driving dataset that is available for public use. For this workshop, we downloaded WiGLE data from the Los Angeles area in order to offer a map view feature to workshop participants. Probe requests that are collected during the data safari can be queried against this dataset to provide information about where the device owner may spend their time.

Tracking People’s Physical Movements

We now know that the passive collection of seemingly banal personal information can result in the 1) identification of human presence and 2) potential reconstruction of past physical location by using a single WiFi card, which supports monitor mode. With multiple WiFi cards positioned throughout a defined area it’s also possible to track the movements of individuals carrying mobile devices. This is a regularly deployed technique by many institutions including shopping centers, hotels, government agencies, universities and small businesses. One notable example was the London based marketing firm Renew which offers WiFi tracking services it describes as “Internet cookies in the real world”. Within a single week Renew was able to track 4 million devices throughout the city by placing sensors in public trash cans. It’s difficult to discern how many institutions deploy such tracking techniques as the act of listening to probe requests is “passive” and can not be detected, but given the interest in such data and the fact that such tools are readily available we suspect it’s very common.

Honeypot & Evil Twin Networks

In addition to the mass data collection and tracking mentioned above, probe requests can also be exploited to execute more malicious network attacks. Because networks are often configured to auto-connect to known networks, an attacker can easily create ad-hoc networks with SSIDs that match those a targeted device is probing for. By forcing a connection in this way an attacker can exploit vulnerabilities in software running on the device to record, intercept, or alter the user’s Internet activity, or perform a phishing attack to steal the user’s account credentials.

Internet service providers have been known to exploit this SSID auto-connection feature in the wild. Comcast’s XFINITY routers automatically create two networks, one to serve the customer who purchased the router, and the second to serve the rest of their customers. This second network beacons with the SSID “xfinitywifi” to lure probing customers to auto-connect. This prompts a captive portal on the user’s device with a form to login to their Comcast account and piggy back of the router owner’s Internet connection to surf the net.

What’s to Be Done?

The picture we paint of the WiFi protocol is fairly bleak. The aging WiFi standard was introduced at a time when the networked landscape was very different than it is now, and yet we continue to expect it to “securely” connect the devices we rely so heavily on today. Though probe requests and beacon frames likely aren’t going anywhere soon, there are a few measures that can be taken to protect yourself from data collection and targeted attacks against your devices. The most effective protection is to turn your device’s WiFi off while in-transit or whenever you aren’t connected to a familiar network. Doing so will keep your device from constantly sending probe requests and make it inaccessible to attackers.

The most effective protection is to turn your device’s WiFi off while in-transit or whenever you aren’t connected to a familiar network.Another privacy mechanism that is starting to be more regularly adopted by device manufacturers and operating system developers is MAC randomization. This approach broadcasts probe requests with a random MAC address, making it difficult to detect the presence of an identifiable MAC fingerprint or to tie multiple probed SSIDs to the same device. More devices are using this method today than we found them to be two years ago, but this approach still isn’t without its shortcomings. Devices that use MAC randomization for probe requests still authenticate to access points using their true MAC address, making the use of honeypot access points an effective method to identify the true MAC addresses.

Have some thoughts to share? Join the public conversation about this post on Twitter, or send us@brangerbriz.com an email, we'd love to hear what you think!